Key Takeaways

- The U.S. ranks no. 1 in the developed world for maternal mortality rates. It also has high infant mortality rates.

- Factors related to race, culture, and geography can affect maternal outcomes.

- Doulas, nonclinical birthing coaches, have proven to be an effective resource for mothers during and after pregnancy.

- A pilot program in Erie County led by New York State formally recognized the value of doula services, specifically for low-income families.

____________________________________________________________________

Being pregnant is both a physically and emotionally intense experience, and everyone hopes for an uncomplicated delivery and a healthy newborn. Unfortunately, a safe and easy birth isn’t always guaranteed in the United States. In fact, the U.S. has the worst rates for maternal mortality and maternity care compared to other developed nations. In 2022 the U.S. infant mortality rate also grew 3 percent, marking the biggest increase in 20 years. The Health Foundation for Western & Central New York is committed to supporting solutions that can help reverse these trends.

High mortality rates

Many factors can contribute to complications during and after pregnancy, including a lack of access to quality health care, underlying medical conditions like hypertension, low socioeconomic status, and a lack of community resources. Health disparities based on race and ethnicity as well as cultural and language barriers can also affect maternal outcomes.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, non-Hispanic Black women are nearly three times more likely to die from complications related to pregnancy compared to white women. This troubling statistic isn’t tied to income level, either. Data show that Black women have a higher maternal mortality rate regardless of their socioeconomic status.

Implicit bias and structural barriers

Danise C. Wilson, executive director of the Reproductive Health Access Project and formerly with the Erie Niagara Area Health Education Center, explains that the medical system itself can unwittingly create barriers. Implicit bias, which refers to underlying assumptions a provider might have about a patient, can cause Black women to receive inadequate care. They’re less likely to receive a high level of communication from their provider, resulting in potential misunderstandings and mistrust.

“It comes down to not being heard by the doctors and nurses, not being believed,” says Wilson. “Imagine wanting a natural birth, but the clinician schedules you for an induction or a cesarean and doesn’t explain why.” Black women are also less likely to have their pain taken seriously, a pattern rooted in inaccurate information and racist assumptions dating back to the days of slavery.

Another structural barrier is that dedicated providers working at busy hospitals and clinics, often understaffed, must contend with heavy patient loads. This is especially true for safety-net hospitals and large clinics that serve patients covered by Medicaid insurance. “Even from prenatal care to birth and delivery, they’ve got you booked in a 10- or 15-minute appointment slot,” explains Darcy Dreyer, director of Maternal and Child Health at March of Dimes NY/NJ.

How doulas provide comfort and build trust

A doula is a trained, nonclinical professional whose services can improve pregnancy, birth, and postpartum outcomes. A doula isn’t the same as a midwife, who is clinically trained to deliver a baby. Instead, a doula is wholly focused on the physical, emotional, and psychological needs of the birthing parent.

As an extension of the care team, the doula becomes the person in the delivery room to provide moral support and advocate for the birthing person. Doulas can’t make any clinical decisions, but they can facilitate communication between the patient and the medical team.

They can also help navigate the emotional rollercoaster of labor. They might give a comforting massage, encourage breathing exercises, or suggest walking around to ease the contractions. If the birthing parent is there with a partner, the doula can give the partner some respite.

All doulas are trained and certified. Some work on their own and serve private-pay clients. Others opt to help low-income mothers.

Having a doula on the care team can create positive maternal and infant outcomes*, including:

- Fewer negative birth experiences

- Increased possibility of a shorter labor time

- Lower preterm birth rates

- Higher rates of vaginal births, including for women who previously gave birth through cesarean deliveries

- Higher scores for a newborn’s overall well-being

- An increase in healthy birth weights

- Increased rates of breastfeeding

- A greater level of confidence and self-empowerment for the mother

*This summary is based on information shared by the Erie Niagara Area Health Education Center, Jericho Road Community Health Center, and the Seven Valleys Health Coalition.

New York State’s doula pilot program

In 2018, New York State’s Department of Health launched a pilot program for doula services in Erie County to expand maternal support for Medicaid-insured patients. At the time, doulas were not being compensated through Medicaid for their services.

The pilot produced significant benefits. Doulas reported that the program allowed them to expand their capacity to serve more Medicaid members. They could support clients by advocating for a childbirth experience that considered their clients’ preferences. The number of families on Medicaid who used doulas increased. The number of vaginal births increased, resulting in lower insurance costs.

Previously ineligible for Medicaid reimbursements, doulas could now receive $600 per pregnancy (eight visits, labor, and delivery). The pilot was expanded statewide, and in 2023, under the leadership of Governor Kathy Hochul, Medicaid reimbursements for doulas more than doubled: $1,500 in New York City and $1,350 in upstate New York.

Erie Niagara Area Health Education Center

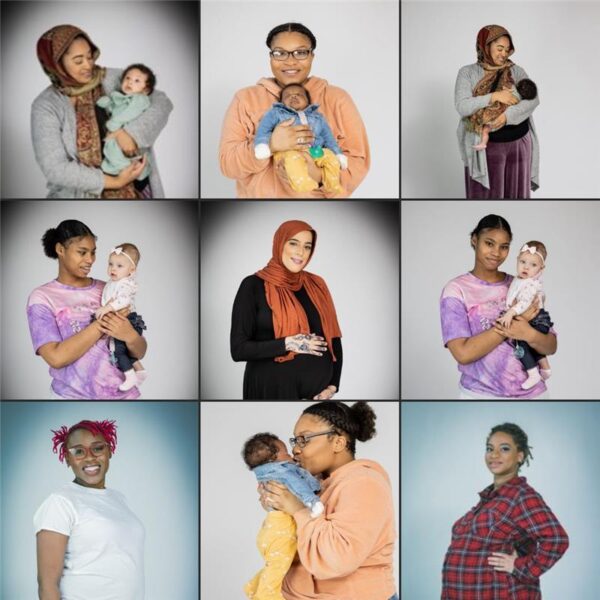

In 2020, the Erie Niagara Area Education Center (ENAHEC), a participant in New York’s pilot program through the support of the Health Foundation, established a doula training program within their Birth Equity Project. “We’re trying to eliminate the health disparities for Black and Brown moms that we see in our community in regard to maternal and infant morbidity and mortality,” explains Madeline Ackley, a project manager.

To grow the doula workforce, the Birth Equity Project is especially focused on training Black women. Other goals include helping doulas navigate the complex Medicaid system and educating both health care providers and the community about the role and value of doula services.

Kalia McCray, who serves as the point of contact for the doulas, looks for compatible personalities. “Birth work isn’t always easy work, and it’s challenging to find a good match between a doula and a mom,” she says.

Once they’ve been trained and certified, the doulas can work independently or through the ENAHEC network as a Medicaid provider. “A lot of people still don’t know what doulas are or that it’s an option for them,” McCray says. “In fact, it’s a right to have a doula.”

Brittany Tranello, executive director of ENAHEC, applauds the program’s reach and the strength of ENAHEC’s community partners. “I do think we have a really good foundation here.” The ENAHEC team gets the word out to the community by bringing flyers to ob-gyn clinics, community baby showers, and community health events. They also hand out information at festivals such as Juneteenth.

Jericho Road Community Health Center

The majority of clients at Jericho Road Community Health Center, another grantee-partner, are immigrants and refugees. Since immigrant and refugee women face unique cultural and language barriers, Jericho Road created the Priscilla Project, providing maternal support such as prenatal education, mental health screenings, mentoring, and language interpretation services.

“We have a huge Burmese population here in Buffalo,” says Sondra Dawes, director of Maternal and Child Health Programs. “We’ve also seen a lot more people from Afghanistan recently.” Other countries include Congo, Burundi, Uganda, Somalia, Eritrea, Nepal, Burma, Ecuador, Venezuela, Bangladesh, and Iraq.

Each Jericho Road community health worker is also trained as a doula. A nurse-practitioner leads a six-week doula training, after which doulas must shadow three births. Once certified, they become part of the Jericho Road staff. “It’s less important to get an already-trained doula and more important to find the right cultural match,” says Dawes. “All of our doulas are paired with clients who speak the same language.” When that’s not possible, an on-demand language interpretation service is used.

About six to eight weeks before the due date, the expectant parent will work with an assigned doula to create a birth plan. The plan covers everything—from anticipating how to manage pain during the birth to choosing the right car seat for the infant.

“Doulas who attended the birth will then check in for feeding visits up until about four weeks,” says Priscilla Project Manager Julissa Vazquez-Coplin. There are also six-week postpartum screenings for depression and follow-up visits for six months.

Cortland County’s doula network

In Cayuga, Cortland, and Madison counties, a collaborative project is making it possible for doulas to help pregnant people in rural communities in central New York.

Gabrielle DiDomenico manages the Cortland-based doula network through the Seven Valleys Health Coalition. The program hosts a lot of meet ‘n’ greets for community stakeholders, including breastfeeding support groups and the local health department. The idea is to explore ways to collaborate, and this involves cultivating good working relationships with the ob-gyn staff members at the local hospital and clinic. “Knocking down the myths and misconceptions about what doulas do or don’t do was a big reason to create our referral network,” DiDomenico explains.

“As the birthing mom, you’re sort of in your own lane, and your partner might be dealing with anxiety. To have that support through a doula is helpful.” She describes one client who had previously suffered a stillborn birth. This time around, with the moral support of a doula, the woman delivered a healthy baby.

DiDomenico stresses the importance of training postpartum doulas as well. Once the baby is here, the doula can be the extra set of hands to help the new mom transition back to home life. Part personal assistant-part social worker, the doula can search for community resources to help the growing family. “A successful mom and child means a successful family,” DiDomenico says. “And that means a successful community.”

The road ahead

The road ahead

The newly increased Medicaid reimbursement rates are a significant first step in acknowledging the role professional doulas can play in maternal health care. We believe the rates should be even higher to help doulas who want to work full-time and keep up with the cost of living.

In her 2024 State of the State address, Governor Hochul introduced a six-point plan to reduce the risks of maternal and infant mortality. The plan includes the continued expansion of doula services for low-income New Yorkers. While important, the measure draws attention to how much more can be done to combat staggering maternal and infant mortality rates in our state.

Whether in large hospitals or small clinics, providers are doing what they can with the resources they have to deliver the best maternal and infant care. But there are still limits to a health care system that too often rewards volume over outcomes.

Doulas are a critical component to solving the maternal and infant mortality crisis—but they’re not enough. A holistic approach to pregnancy and childbirth across the health care system is also needed.

To learn more, read the March of Dimes 2023 Report Card for New York State

Photos courtesy of Erie Niagara Area Health Education Center, Jericho Road Community Health Center, and the Seven Valleys Health Coalition.